Business Standard, 6 min read Last Updated : Jan 01 2024 | 10:42 PM IST

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) has been one of the major policy successes of recent years. It has stimulated the growth of a truly national market, by replacing a welter of distorting taxes with a single rational system. It has also provided a stable source of revenue to both the centre and states, notwithstanding some teething issues and discord between the two levels of government. But how much has the government actually received from the GST? Is it really an improvement on the pre-GST regime? The answers are surprising.

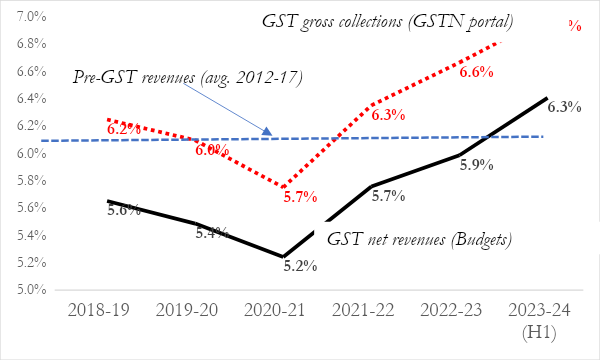

Nearly all analysis of GST, whether in reporting by journalists or research by economists, is based on the data from the GSTN portal. In both the portal and the analysis, including some excellent recent academic studies, the GST figure reported for 2022-23 is Rs 18.1 lakh crores, equivalent to 6.6 percent of GDP.

But this figure actually measures GST collections, and collections are not the same as government revenue. That’s because some of the collections are refunded to taxpayers. And these refunds are not a small matter. In 2022-23, the last full year of data, they amounted to no less than Rs 1.8 lakh crores. As a result, government GST revenues (both centre and state, including the cess) amounted to Rs 16.1 lakh crores or 5.9 percent of GDP, about 0.7 percent of GDP less than what the headline number suggests.

Figure 1 shows that last year’s difference between collections as reported by GSTN and net revenues after refunds accruing to the government was not a fluke. Ever since the GST was implemented, this gap has hovered around 0.6-0.7 percent of GDP.

Figure 1. GST: Gross Collections versus Net Revenues (% of GDP)

The large amount of refunds has important implications for how one views GST performance. Gross collection data gives the impression that the GST regime immediately overtook the pre-GST average (the dotted line in Figure 1, as calculated by Prof. S. Mukherjee in a recent NIPFP paper), then dipped during the pandemic period, and once again surpassed the pre-GST regime in 2021-22. But revenue figures tell a very different story. They reveal that GST revenue overtook the pre-GST regime only in the current fiscal year, six years after the tax was first implemented.

If the refunds make such a material difference to the GST story, why have they been ignored? Perhaps because the GSTN does not publish the refunds data. As a result, we can only infer the numbers by comparing the gross collections reported by the GSTN with the revenues in the central and state government budgets.

What are these refunds? GST refunds are different from those on individual and corporate income taxes. With income taxes, there are advance tax payments, which require ex post reconciliation and hence refunds. But in the GST, taxes are paid on actual revenues, net of the taxes actually paid on inputs. So, in most cases there is no need for refunds.

There is one major exception. In the GST, exports are zero-rated, which means that exporters don’t pay taxes on their output but are entitled to refunds on the taxes they paid on their inputs. This constitutes the major chunk of refunds under the GST. (Recall that zero-rated items are different from exempt items, which are not taxed but which are also not entitled to input tax credits).

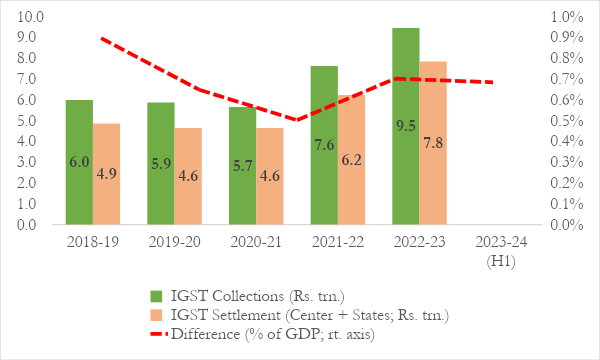

At the same time, refunds are related to the IGST. The red line in Figure 2 shows that the discrepancy between IGST collections and IGST settlements (the amounts actually distributed as revenue to the centre and the states) is remarkably similar to the gap between overall collections and revenues shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2. IGST Collections and IGST Settlement (Rs. trillion) and Difference (% of GDP)

Note: IGST settlement to the states includes ad hoc settlements which were discontinued in October 2022.

Putting the pieces together, it seems that the gap between collections and revenues reflects refunds paid to exporters to reimburse them for the IGST they paid. We can hypothesize, but cannot be sure, that this IGST relates mainly to imports used in production, rather than goods imported from other states. (Other data suggests that many exports, such as iPhones, rely heavily on imported parts.). In other words, the refunds are given mainly to compensate exporters for the IGST paid on their imported inputs.

Is the fact that GST revenues have only recently surpassed pre-GST levels an indictment of the GST? Not at all. Revenues have declined for two reasons. There was a rate-cutting spree in the years leading up to the pandemic, which reduced the weighted average collection rate from 14.4 percent in May 2017 to 11.6 percent in September 2019, according to the RBI. Another reason for the decline in revenues was that export refunds became much smoother, quicker, and fuller with the GST than they were under the previous regime. This is surely a good thing.

That said, the revenue data suggests we need to focus on further boosting GST collections. At this point, there is little room to improve administration without risking over-zealousness and unnerving taxpayers; the real need is to address the two remaining major design flaws. The rate cuts of 2018 and 2019 need to be reversed, even if not fully, as part of a rationalization of the overall rate structure. The second problem is the inordinate complexity in rates, especially for the cesses, which probably drags down revenue collections and certainly complicates enforcement.

The most natural change would be to move to a three-rate structure (recommended by the RNR Committee in 2015) with a standard rate of 18 percent, a lower rate of say 10 percent and a demerit rate of 40 percent. And if GST compensation is a thing of the past, the now-redundant cesses should be incorporated into the normal rate structure at the top rate of 40 percent. Not only would such a move simplify the system; it would also eliminate a major distortion whereby a significant source of revenues has been walled off from the standard divisible pool of taxes that provides resources for both the centre and the states.

Three conclusions follow: The GST did less well in the initial years than we have thought, but is now doing much better than we could have hoped for. It could do even better if it were redesigned in the direction of simplicity. And our appreciation and understanding of this historic reform would improve if the refunds data (and their composition) were to be published.

...

Disclaimer: The article first appeared in Business Standard. The publication details along with the link to the original publication is given above.